Incubating future movements in travel and culture

Words Emily McDermott Images Daniel Lober

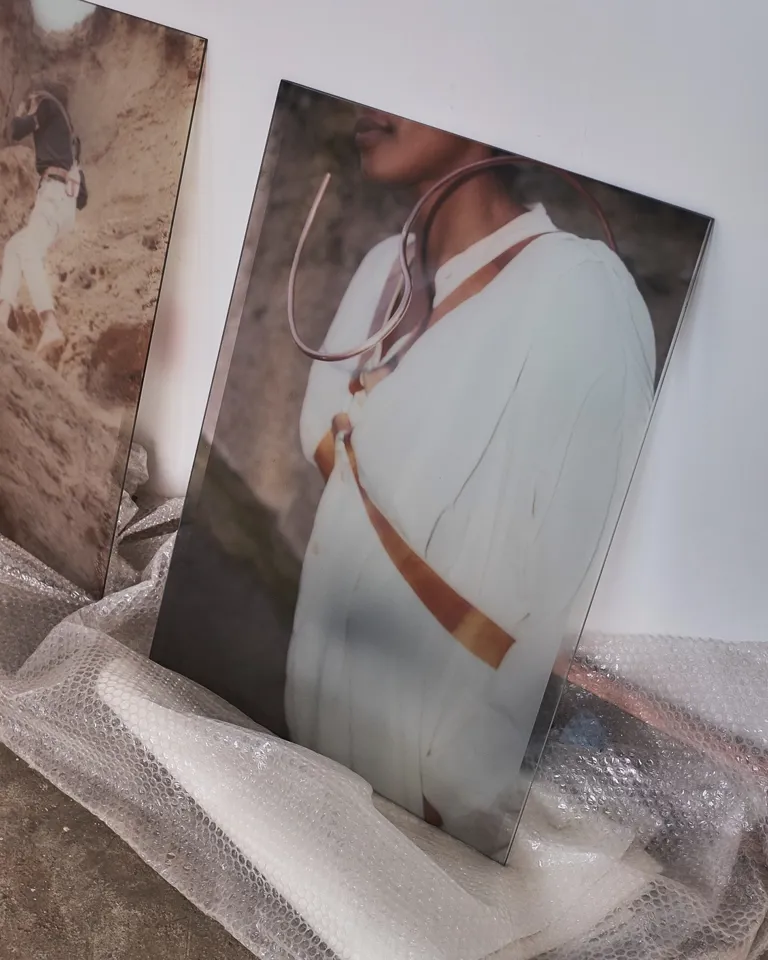

From car racing and hip-hop music videos to abandoned airports and arenas, Berlin-based artist Lena Marie Emrich focuses on the marginal and the social throughout her multidisciplinary practice. She interweaves media like performance, photography, video, art in public space, and sculpture to shed new light on unique characteristics of these communities. While in residence at La Pause, Emrich collaborated with local glassblowers, metalsmiths, and leather specialists to create a new body of work inspired by the landscape and the meteorology of the Agafay Desert, resulting in fragile yet wearable copper, glass, and leather sculptures that evoke notions of bondage as well as running gear designed for marathons. In a final exhibition, the sculptures were displayed on a table but also appeared in photographs depicting a man wearing them as he wandered through the desert. Here, Emrich expands upon her inspirations, her collaborations, and how she was seduced by the desert.

Lena Marie Emrich: It all started one night when, after a week of sun, it started to rain. I opened the windows and could smell the mineral ground so intensely. The scientific name for the exact moment when the first raindrops hit the ground is the “petrichor,” and this moment really struck me. Over the course of the last year, I also started researching the alignment and delimitation of human and nature, so I was very inspired by the riverbed, which is almost dried out, and the fact that you can sense the water structures in the desert, even if the water isn’t there anymore.

Also, when coming from a city into the desert, your gaze has this moment of relaxation: When I looked around, there was this blank, nude landscape. I was reminded of a naked body. There are the forms of the mountains and their roughness and broadness, and for me that’s an erotic landscape. Every evening, I also ran in the almost-dried-out riverbed, where you can see layered stones, which are the layering of time—an archive of centuries.

You are seduced by the desert, by the forms of the mountains and the structures of the layered stones. But at the same time, we, as humans, always have a need to dominate nature. I wanted to bring these two different concepts together in my work, which is how I came up with the idea to play with bondage culture and to create the “petrichor hydration gear.” It has elements of warrior gear, of bondage, and of a hydration system normally used by runners. By creating the hydration packs, it became less erotic and more casual.

Lena Marie Emrich

LME: I decided to work with leather because it can be seen as a second skin—it takes the temperature of the body—but I also wanted to create a structure which mimicked the landscape. So, I decided to get natural leather and recreate the structure of the layered stones in the riverbed through pigmentation. To connect the pieces, I decided to work with glass, the sand for which comes from the center of the riverbeds. The third element is copper because in ancient times, it was used to insulate water, and now, if you're at a nice cocktail bar, you might be served a Moscow Mule in a copper cup. With my work, I like to play with ancient materials but bring them back into a contemporary context.

Emrich collaborated with local glassblowers.

LME: It was interesting because we drove directly into nature and detached from society for a bit, but, at the same time, we experienced Marrakech through the eyes of Roxane [Alaime, founding director of La Pause Residency], who grew up there. So, we were connected with locals from the very beginning. We didn’t have a touristic experience.

It was also amazing to meet the artisans, to see their workshops, and to really experience how they work, because sometimes we lose our relationship with everyday objects and how they’re produced. For example, there are these very traditional beldi glasses that you might find in restaurants in big cities, but you’d never think about where they come from. In Marrakech, we went to a glass factory and saw how they are manufactured, one by one, by a guy blowing the glass. The residency made me aware of everyday objects, how they are created, and how they have their own souls. It made me question myself in my usual urban landscape and how I become detached from my surroundings.

Emrich's contributions to the final exhibition at Pikala Bikes included her poetry etched onto the walls.

In Emrich's artwork, glass rings found in a glassblowing workshop were transformed into sculptural objects.

LME: I like to dive into subcultures with my work, so my practice is based on collaborations and talking with people. Every person I collaborate with is very important for the project. And artists are nerds; we are trying to dive into and explore different scenes. Artisans are also nerds; they are specialists in one specific material, and they know it to the very end.

It's nice to meet artisans and to share ideas. If you have any doubts about what you’re doing, you can talk with them — they know the material better and can help you. For example, I was designing a copper bottle and I had an idea for the form. Then I was talking to a coppersmith about how to make it happen: How do we close the bottle? What is the best system for that? We were figuring out how to improve my design. I'm always open to changes in order to make the best object in the end—and that can only happen if you work with a specialist. I felt like every artisan I worked with was also feeling the idea and trying to help me realize it in the very best way. They were creating the work together with me.

LME: It’s important for me to use my hands because I studied sculpture for six years, so normally I do my things myself, and if I give it to a person, I like to be next to them and see how it evolves. But in Marrakech it was different because I gave the work to the people and I also left at some point because we had other things to do. When I came back and saw the leather, glass, and copper objects, it was just like, “Wow.” The coppersmith, for instance, had found the perfect solution for a copper frame to hold my photographs printed on glass. These moments—when a collaboration expands the work—are amazing.

Further Marrakech

In collaboration with La Pause Residency, Further Marrakech asked what it means to be an artist or an artisan—and what happens when such practitioners come together in the act of creation.

Further Marrakech

M’Barek Bouhchichi is unlearning the Euro-centric history he was taught in favor of understanding and documenting his country’s context, history, and people through his artistic practice.

Further Marrakech

Running in a nearly dried-out riverbed moved Lena Marie Emrich to create glass-plated photographs and bondage-inspired leather sculptures.

Further Marrakech

From building hospitals to overseeing large-scale exhibition programming, sharing knowledge is the most important aspect of everything Amine Kabbaj does.

Further Marrakech

Moroccan artists Loutfi Souidi and Mohamed Arejdal believe the future lies in the local past and the global present, and, more importantly, the connection between the two.