Words Ken BaronImages Manuel Zúñiga / Hotel Images

After receiving his undergraduate degree in architecture and economics, he was working with developers in Mexico trying to implement sustainable design into large-scale developments. “The reaction,” he explains, “was always ‘No. No. No.’” And then after attending grad school at Stanford University, things didn’t change that much, “I was presenting developers with architects who would go the extra mile and try to incorporate sustainability, like passive conservation-driven systems, and again it was ‘No! It’s not worth the effort.’”

Set on Bacalar lagoon, Boca de Agua is designed to have a minimal impact on wildlife

While most people tend to accept their fate, Juarez understood that the only way to free himself from his web was to do something drastic. “I was just not in a great place, personally and professionally. I had created this false narrative with false expectations about what my life should be like. Moreover, I realized that I was only truly at peace when I went camping or hiking, when I could leave my phone behind and be in nature. So, I contemplated taking a long backpacking journey across Mexico. I know that’s not so rare, but for me, a former overachieving career-focused young professional, seeing my former classmates thriving in their own careers, and posting their successes on LinkedIn and Facebook, it would be a huge leap. So I quit my job and said, ‘I’m going to start from scratch.’”

Today, that leap has brought about Boca de Agua, immersed in the natural wonders of the Yucatan Peninsula along the Mayan coast of Quintana Roo, Mexico. We sat with Juarez to discover how a man from Monterrey, Mexico, became a visionary in a jungle near Bacalar.

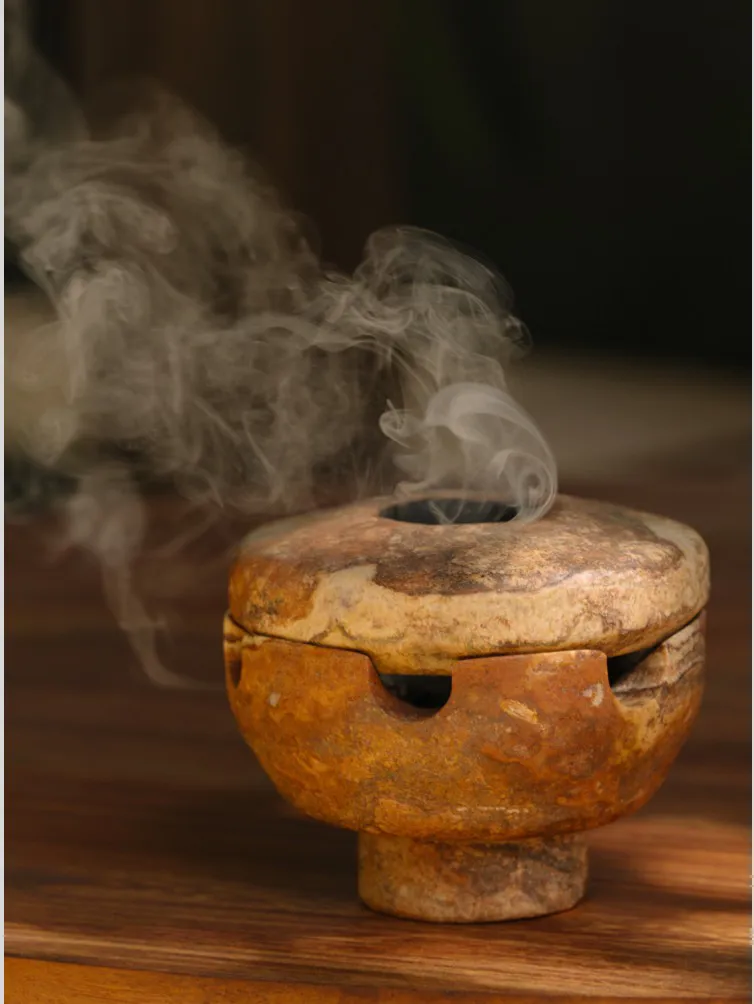

Wellness on the water: Breathwork and meditation are part of the hotel's sunrise paddleboard experience

There is a quantitative and qualitative aspect to every project, and the qualitative is really hard to measure. Still, it’s no secret that projects that are well-designed and incorporate nature tend to be more financially successful than those that only care about square meters. After my frustrations in the architecture world, I wanted to be on the project development side so that I could take the lead on both the creative and financial aspects of the development process. Yes, it can be more expensive to build projects that implement sustainable practices, such as using natural materials—but, from a business perspective, most of those things are actually worth it.

I decided to go to business school, to Stanford, and focused on a dual MBA-Engineering course-track called Sustainable Built Environments. It’s a very engineer-y/scientific program that I combined with general business know-how.

Mayan ruins served as an inspiration for Boca de Agua’s communal layout

Oh no! After grad school, I ended up, like most of my classmates, at a desk job crunching numbers and making PowerPoint presentations. It was not the right environment for me—but I wanted to get real experience building financial models and business plans from scratch and pitch them to investors and banks so that I could make projects like Boca de Agua a reality.

Absolutely. I was able to put together a sound financial model, get investors on board, get financial institutions to fund the construction—Boca de Agua has a big government-sponsored loan that’s given to small, independent, sustainable projects in eco-tourism. People assume the most challenging part of creating the hotel was the construction or the environmental restrictions. And yeah, those things were tough. But by far the toughest was creating a viable business plan where I didn’t have to compromise on my ideals.

It did. The trip made me realize how little a person needs to feel fulfilled. I was living under the shadow of social comparisons—I was looking at what other people had and started to think that I needed all of that too. But I discovered that this was absolutely not true. And that’s when I started focusing on doing something that would feel authentic to who I am: a hospitality venture that intersects design, culture, nature, conservation, and good business practices. These aspects really matter to me, and with that realization I started conceiving and shaping this beautiful project that has now become Boca de Agua.

Set in southeastern Mexico, near the Belize border, the town of Bacalar is a culturally rich haven

On my backpacking trip, I explored all of Mexico from coast to coast. Bacalar, right on the border between Mexico and Belize, was the last place I visited, and I completely fell in love with this place!

Yes. In Bacalar, it was almost impossible to find a big enough piece of land to develop where I could implement the conservation aspect that I was after. After dealing with brokers, I became good friends with the receptionist at the hostel where I was staying, and she told me that her uncle had this beautiful property but that he didn’t want to sell it. I ended up having breakfast with him twice a week for a month. I told him about my vision. And he was like, “Ok, if you are going to do a project that truly preserves what I’ve worked to preserve for decades, we can make something happen.” I didn’t have the financing back then, so we agreed on a three-year payment plan. He was very helpful and I kept my word: 90% of the site remains a natural reserve.

Native to the Yucatan Peninsula, the iguana is one of over 180 species of reptiles and amphibians that can be found in the area

Most people who come to the hotel for the first time can’t believe what we have built here—the scale of the treehouses, the mostly untouched jungle, the amount of wildlife roaming around freely, the sun hitting the Caliza stone façade in the afternoon, the intense Caribbean blue lagoon. And to those same people who ask how I did it, my answer relies mostly on one main factor: ignorance. I think the older we get, the wiser we become. But the wiser we become, the less risks we are willing to take, and our awareness of how painful and difficult certain endeavors can be, increases. This project exists in great part thanks to my inexperience, my youth, and my ignorance of the challenges that lay ahead of me.

A lot had to do with the hotel’s architect, Frida Escobedo. We met in 2014, and even back then we agreed that one day we would do a project together. So, with Boca de Agua, Frida and I started thinking about treehouses made of wood. That would serve our purposes from a conservation standpoint because the impact on the ground is minimal, and the local fauna can roam the ground unaffected. But also, by elevating the structures, you get more natural light, more natural ventilation…so from a sustainability standpoint, it checked all the boxes.

The architecture at Boca de Agua blends seamlessly with its natural surroundings

Rodrigo Juarez

In all honesty, I really admire the raw talent in some architects; it’s a gift, and I don’t think I have that, or at least, not yet. But I think my schooling made me a very good critic, and with Boca de Agua, I wanted to collaborate with someone with more experience and more confidence in their design process. I’m doing more designing now, but only after learning so much from Frida. Having her onboard, leading the process, was very special for me.

Well, that gets back to the realization that came during my backpacking trip, the idea that you don’t need much to feel whole. For me it’s about being connected to nature, about having that “aha” moment. You feel better mentally, physically, in every way. I want my guests to leave Boca de Agua feeling that they were in a place that allowed them to pause and breathe and write and read and connect to whatever is important in their life.

Juarez finds solace in the calm lagoon waters

The sunrise in Bacalar is among the most beautiful in the world. The lagoon is this insane blue color, and the water is so still in the morning, like a sheet of ice. We take our guests on a sunrise paddleboard experience to the middle of the lagoon to do breathwork and meditation. Every time I’ve done this, it feels very transformative and healing.

I emphasize science because I think the term “wellness” is sometimes overused. I like to focus on the immediate effects of simple wellness practices—for example, what very basic human needs such as balanced diets and exercise does to your body long-term or what learning to breathe properly and meditate for at least a couple of minutes a day can do to your mental and physical health.

My answer will be a little strange because it’s someone who won’t remember me. I was doing an internship in San Francisco at a company that produced sustainable social housing and architecture all in one shop. I remember the founder of the firm would work a full day and then go into the basement of the office to a ceramics workshop that he had built there. He’d stay there for hours. His company was not doing very well at the time, but he was the coolest, nicest, most chill guy. I remember him saying, “Life is too short to not do the stuff you love.” That really stuck with me for two reasons. One was the sense of peace that he had even when his business was going through a tough period. And two, he wouldn’t skip his ceramics at the end of the day because he just loved it so much and brought that much needed peace to his day-to-day.

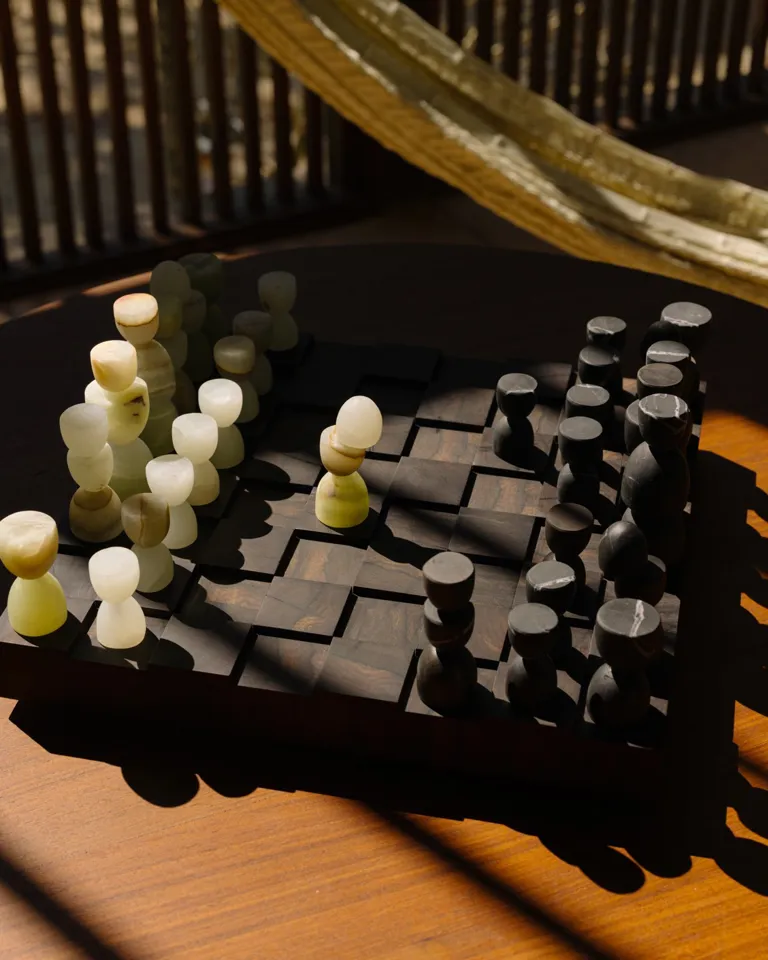

Yes. The designer in me still loves to design things. It doesn’t have to be buildings. For example, right now I am designing a chess set, which is great because you get to create each piece and then create some contrast with the board. Plus, I really enjoy chess. It takes your mind off things, off your phone. It’s this very heavy thing made out of discarded wood from the construction of our treehouses.

A passion project: Juarez’s hand-carved chess set

I’m getting better and better! I definitely have more reasons to be stressed and anxious, but I’ve gotten more adept at managing them. Also, being in this natural paradise that is Bacalar really helps.

The response has been incredibly positive. All our collaborators are from the area, or at least they have been living here for many, many years. They feel an enormous sense of pride to say that their place of work is Boca de Agua. And in terms of businesses, we collaborate with the local community in every aspect possible—from food sourcing and consumables, to wellness practitioners. We know that we are part of a community and we act accordingly. We want to have a positive impact in the region.

Rodrigo Juarez