Words Allison Reiber DiLiegro & Ken BaronImages Marco ArgüelloVideo Konstantinos Sampanis | Séance studio

“If I think about my life as it used to be, it feels almost like a fairy tale now,” Aristides says. “But in the early days, I was struggling just to get by.” Today, Aristides is known for his distinctive architectural style, which earned him a place on the European Centre for Architecture Art Design and Urban Studies’ 40 Best Architects Under 40 in 2017. He is also the creative mind behind Pnoēs Tinos, a three-villa gem on the Cycladic island of Tinos.

After earning his degree from the National Technical University in Athens, Aristides honed his skills at an architectural firm and a French home décor brand in the city. But he still had a deep desire to follow his own vision. In 2014—when his first daughter was just one month old—he made the bold decision to move to Tinos and establish his own architecture studio in the midst of one of Greece’s most significant financial crises. Despite the challenges, Aristides remained committed to the architectural principles he believed in, and gradually turned his vision into reality. He opened a second studio in Athens, allowing him to expand his work across Greece.

In 2022, Aristides embarked on a new adventure: designing and building a boutique hotel. “I’ve always been more of a traveler than a tourist, and I’ve admired the hospitality industry for years,” he explains. “Working on this project was a real learning experience for me. I had the rare opportunity to wear many hats: I was the designer and architect, the contractor—physically building the hotel with a team—the marketing director who developed the brand’s name and philosophy, and finally the client, paying for everything and bringing the vision to life!” he says with a smile. “Going through all these stages helped me see things from my clients’ perspective in a new way. It was not just a fulfilling experience; it also pushed me to keep evolving and improving while enabling me to better serve my clients in the future.”

Tinos from above

The journey to perfection

Aristides Dallas

When I was around five years old, I visited a vacation complex with my grandparents. I remember being struck by how different it was from any other building I had seen. It sparked curiosity in me, leading to a flood of “why” questions. My grandma, after trying to answer them all, finally said, “Because an architect made it.” That simple response left a deep impression on me and planted the seed of becoming an architect myself.

In Greece, we have a tradition where your godmother gifts you a special candle for Easter. That year, I asked her for a candle with a ruler on it—something that, to me back then, symbolized the act of measuring buildings. From then on, I began to look at buildings with a more attentive eye, imagining how I could design spaces myself one day.

Employees and students always have a place to express their ideas

Sculpture by Greek-Tinian artist Christos Santamouris on display in Aristides’ studio

Office building in Athens by Demetrios Issaias - Tassis Papaioannou, Architects

When you’re a child, everything is a mystery—you’re full of questions and wonder. But it’s not until you start studying that you begin to see the world with more understanding. For me, university was truly life-changing. It opened my eyes to the deeper layers of what architecture really is.

In my first class at architecture school in Athens, the very first exercise was to simply go outside and observe—just look at the city around you and take notes on whatever catches your attention. Later, we would go out with the professor, who would point out things we had overlooked. This simple exercise taught me to see beyond the surface and notice the details that make up the fabric of a place. Little by little, you begin to develop what I would call an “architect’s eye,” a way of seeing that shapes everything you do.

Dallas sees purpose and form amid a haphazard skyline (above) and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center (left)

When I started university, I felt an intense need to explore the world beyond my studies. At 19, my family faced financial difficulties—my father went bankrupt. To keep studying and pursue my passion for travel, I took on two jobs. I spent twenty hours a day working and studying, with just a few hours left for sleep. But whatever little extra money I earned, I saved for travel. I made it a priority, taking trips to America, Asia, and many other places. These experiences truly shaped me. They opened my eyes to different cultures, perspectives, and ways of living, which in turn helped me grow both as a person and as an architect.

I believe that an architect needs to understand two fundamental things: the client and the place. It’s easy to fall into the trap of designing something that reflects your own vision more than the client’s needs—something I found myself doing in my early days. When you’re full of enthusiasm, it can be difficult to find the right balance. But with time, you learn that the real art of architecture is in letting go of your own ego and allowing the project to fully belong to the client.

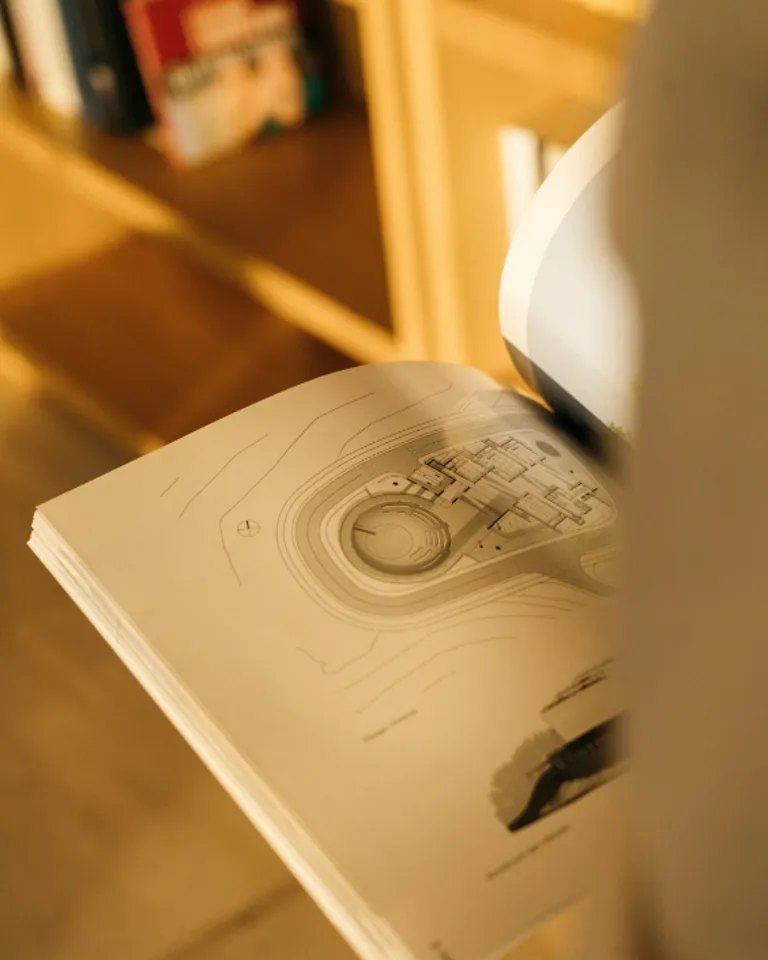

Earth, wind, and water: The landscape of Tinos inspired the vision behind the hotel

Nature in the Cyclades

Aristides Dallas

Letting go is a bit like watching your child grow up and move out—it leaves a certain emptiness. When you design a building, you pour your heart into every detail, nurturing it through every stage of construction. But then, once it’s finished, the client steps in and starts making it their own. They might add furniture you wouldn’t have chosen, or rearrange the layout. It’s a strange feeling, watching something you’ve cared for so deeply change in ways you didn’t envision. But this is also where you find beauty—seeing how your creation evolves to meet the needs and personalities of those who live in it.

Location is the second key element. To design a building that truly belongs to its place, you need to understand everything about the location: its history, culture, landscape, climate, and the orientation of the plot. It’s like assembling a puzzle with many different pieces. You also have to think about the future—how the building will interact with its environment as time goes on. This understanding of place, combined with a deep connection to the client, is what allows a building to truly resonate with its surroundings and the people who inhabit it.

Dallas’ projects flow from the landscape.

I often ask myself: What if this design were repeated across an entire city? If we copied and pasted the house we designed, what kind of city would that create? This thought experiment helps me consider whether it’s okay for things to evolve in this direction or if we need to approach it with more humility.

Today, we see more and more architects in our country creating extreme and provocative designs. The allure of creating something spectacular in architecture is undeniable. Spectacular buildings can capture attention, inspire awe, and serve as landmarks. However, they’re like fireworks—brilliant and captivating in the moment. But just as fireworks are fleeting, the impact of purely spectacular architecture can be short-lived if it doesn’t also serve a deeper purpose or integrate well with its surroundings.

Architecture, by its very nature, remains on this earth for a long time. It becomes part of the fabric of our cities and landscapes, influencing how people live and interact with their environment. That’s why, as architects, we have to think beyond the immediate “wow” factor. We need to consider the long-term implications of our designs. A city filled with spectacular buildings might lose its sense of cohesion or, worse, become overwhelming and exhausting for those who live there.

True architectural success lies in creating spaces that balance beauty with functionality and spectacle with subtlety. Buildings that not only impress at first glance but also serve their purpose over time, blending harmoniously with their environment and enhancing the daily lives of the people who use them. It’s about creating lasting value, not just fleeting moments of brilliance.

This kind of thinking is essential when you’re creating something that will stand on this earth for generations. It requires a certain humility—to understand that while we can create extraordinary things, they must be thoughtfully integrated into the larger context of a city, a landscape, or a community. The future of architecture isn’t just about making bold statements; it’s about crafting spaces that people will love and cherish long after the initial awe has faded. I strongly believe that as architects, we hold great power in shaping the future, which also carries great responsibility. We should always respect that.

Tinos was a great “teacher” to me. When I first moved there, my experience had been mostly in urban environments. So, I made it a point to explore the island deeply, to find inspiration in the small details of its landscape and architecture. Tinos taught me the importance of incorporating subtle, local elements into my designs, to create buildings that try to truly belong to their surroundings. Working in Tinos was a great lesson in respecting and understanding the character of a place, and in how the smallest details can make a big difference in connecting a building to its environment.

I don’t have a specific dream project, but I do have a dream to work on projects with a significant social impact. One day, I’d love to design something like a school or a hospital—places that serve the community and improve lives. For me, the true measure of a project’s success is in how it enhances the well-being of the people who use it. Projects like these allow architects to focus on creating spaces that are not only functional but also nurturing and inspiring for those who interact with them daily.

That’s an interesting question. Honestly, it’s hard to imagine being anything else. I truly love being an architect; it’s such an integral part of who I am. Architecture allows me to combine creativity with problem-solving, and it’s difficult to think of another profession that could offer the same fulfillment.