Words Charly WilderImages Vivek Vadoliya for Design HotelsDate 28 October 2020

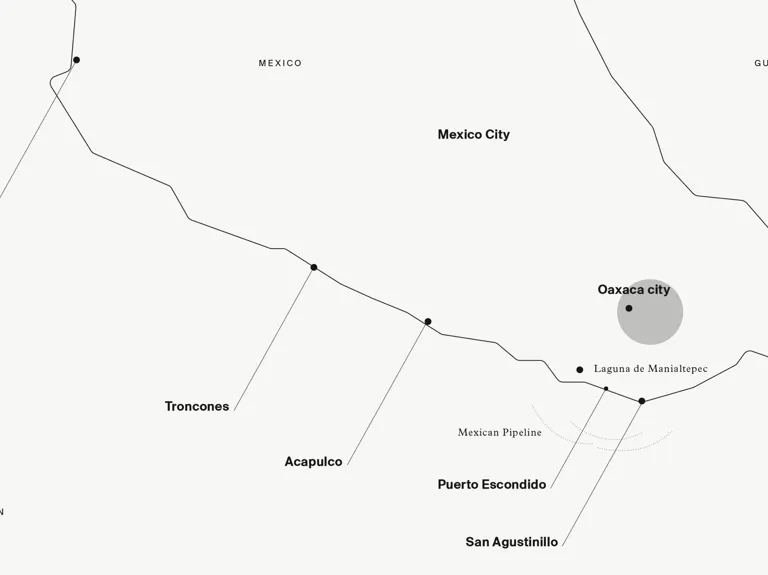

That’s how Oaxaca city had been described to me: the most Mexican place in Mexico, and as soon as I arrived in the centuries-old historic center, I felt like I understood. Low-lying Spanish-colonial façades in bright blues and greens, deep ochres, and poblano reds lined gridded cobblestone streets that opened onto grand squares where musicians played marimba and mariachi at the foot of Mexican Baroque churches.

Hotel Escondido Oaxaca Housed in a colonial residence from the 19th century

Escondido Oaxaca Architect Alberto Kalach bisected the structure with a concrete tower

In the midst of all this is Grupo Habita’s latest addition, Hotel Escondido Oaxaca, which opened in December 2019 in a colonial residence dating back to the 19th century. Typical to building styles at the time, the house wraps around a central open-air patio. Together with a team of local artisans, renowned Mexican architect Alberto Kalach bisected the structure with a thick poured-concrete tower and built in guestrooms, a restaurant and bar, a rooftop pool and garden. Local, traditional, and organic materials were used throughout, from quarry stones and sabino wood to the plant-based paint on the walls.

“The wood, the brick, the plants that we brought in, it’s all from no more than a few hundred kilometers away,” said Etienne Simonin, the general manager of the hotel who has helped oversee its transformation. Escondido Oaxaca, he explained, “was conceived from the very beginning as a hotel that would incorporate the craftsmanship, culture, and spirit of Oaxaca.”

Wild cotton species Mexico is home to the greatest diversity in the world

Oaxaca city Mercado 20 de Noviembre

That Oaxaca is considered the craft mecca of Mexico should come as no surprise. The state is home to the greatest concentration of Mexico’s indigenous people and tribes, many of which have deep craft traditions that converge in the capital. To better understand this heritage, we began the next day with a visit to the Rufino Tamayo Museum of Pre-Hispanic Art, just a few doors down from the hotel, which holds the phenomenal personal collection of the modernist Oaxacan painter Rufino Tamayo, one of the great Mexican artists of the 20th century. Like his contemporary Diego Riviera, Tamayo devoted his life to collecting Mesoamerican art in order to save it from exportation and illegal traffic. The work in the museum is stunning: ceramic votive offerings depicting fecund fertility goddesses and gods of the Mayans and Aztecs, as well as the Oaxacan indigenous peoples, the Zapotecs and Mixtecs.

From the museum we headed to the great labyrinthine markets near the Zócalo, or central square, beginning with the Mercado Benito Juarez, threading our way through aisles lined with piles of fresh produce, baskets of grasshoppers flavored with chili and garlic, handcrafted objects, stacks of dried chilies, and great dark mounds of mole paste. Next door, at Mercado 20 de Noviembre, we encountered an even greater array of artesanías, selling handcrafted huaraches (leather sandals), embroidered blouses, and barro negro pottery. The variety, quality, and affordability was dizzying. But we were soon to find out that Mercado 20 de Noviembre is also one of the best places in the city (if not the world) to have lunch.

“We have to go to the smoke hall,” said Daniel Mendez Gaytan, an experienced local guide who serves as guest ambassador for Escondido Oaxaca. “That’s what locals call it.” He guided us to one side of the market, and we made our way down a long hallway that was, quite literally, filled with smoke. On either side of the corridor, brawny men labored over giant barbecue grills next to which they displayed huge cuts of raw meat.

Guitarists snaked their way around the tables belting out old Mexican ballads; families laughed and shouted and called out orders. The meat sizzled and smoked, and every few minutes someone would clap for tortillas.

Exploring the markets, it was easy to see why the city has been drawing artists and expats from all over the world. Oaxaca’s rich culinary and craft traditions, as well as its tropical climate and affordability, make it a kind of artists’ paradise. “The art scene is becoming more global,” said Polo Vallejo, a 35-year-old artist and printmaker at La Máquina Taller de Gráfica, a gallery and printshop that’s home to a rare Parisian print machine from 1910. As the afternoon sun streamed in the windows, we watched printmakers labor over the huge machine, creating a print made in collaboration with a visiting artist from New York. “The new generation and these old-school guys are working side by side, so we’re making something different with the old traditions,” added Vallejo. “If you want to be an artist, Oaxaca is the best place to start.”

Oaxacan painter Guillermo Olguín in his sprawling indoor-outdoor home studio

Noel Garcia Sosa A fourthgeneration weaver in the village of Teotitlán del Valle

Our last day in Oaxaca, we left the city and headed deep into the Oaxaca Valley, past rolling, sun-baked fields of agave, where tiny traditional villages, many inhabited for millennia, are known for their traditional artisanship. Many of the villages specialize in a particular type of folk art or handicraft: San Martín Tilcajete is famed for its colorful woodcarving; Santa María Atzompa has been producing pottery since ancient times. In the legendary weaving village of Teotitlán del Valle, we watched as a white-haired fourth-generation weaver named Noel Garcia Sosa worked over a large, traditional wooden loom in the open air as his dog slept at his feet. Garcia Sosa only uses wool from the sheep of Oaxacan Mixteca, he said, and weaves according to his own design, drawing on Zapotec, Mexican, and modernist influences. “It’s all I know,” he said, passing his hands over the same loom his father used, the one on which he now trains his son. “This work belongs to me, and I belong to it.”

Hierve el Agua 65 kilometers southeast of Oaxaca

Oaxaca Valley Scenes

Hierve el Agua Petrified waterfalls

We drove deeper into the countryside and up into the mountains to see Hierve el Agua, a cluster of natural rock formations and mineral-rich hot springs that resemble cascades of water or the surface of an alien planet. We stopped for a drink at a roadside mezcal distillery, where agave was crushed under the hoofs of a donkey, then roasted in a big earthen pit and soaked and fermented in wooden vats before it was bottled and served. Called the “elixir of the gods” and traditionally thought to have otherworldly healing powers, mezcal has been growing in popularity outside of Mexico over the past decade. These days, you can order it in almost any hip bar in Europe or North America, most of it exported from Oaxaca. But there’s another kind of magic when you drink it here on a mountain with the people (and donkey) who made it.

Our last stop was Monte Albán, the ruins of an ancient center of Zapotec and Mixtec culture that sits on a mountaintop overlooking much of the Oaxaca Valley. Believed to date back to the 8th century BCE, it contains great plazas, truncated pyramids, ball courts, figurative monuments, underground passageways, and about 170 tombs. Many believe it to be the first instance of city planning in all of the Americas. I walked among the great earthen pyramids, which, despite the erosion of millennia, seemed to communicate a sacred topology, an expression of sublime ferocity that was both indescribable and yet somehow, impossibly, manifest. From here, you could see down into Oaxaca, the city I had so quickly come to love, the city where this ancient heritage seemed still to live, to transform, and to be born anew.

The preceding article is excerpted from the 2020 edition of Directions, an annual magazine by Design Hotels that looks at movements underway in art, design, food, wellness and fashion, and how they affect the way we live and travel. This year’s issue explores the motivations, values, and desires of the Promadic Traveler of tomorrow—one who does not ask where to travel, but why.