Words Charly WilderImages Vivek Vadoliya for Design HotelsDate 23 October 2020

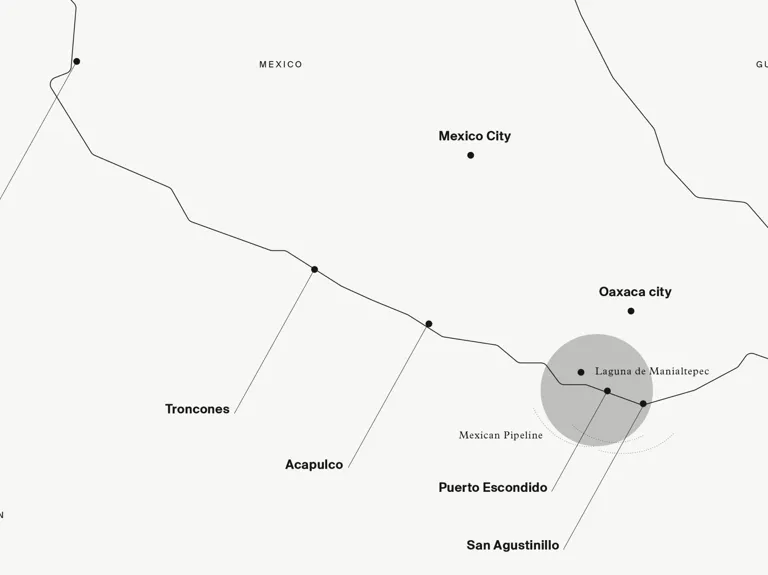

When I first began planning a trip to western Mexico, I imagined an epic road trip: zooming down coastal roads in a car—hopefully convertible, ideally vintage—with the sun at my back and the wind in my hair. Or barring that, a nice public bus. But the distances were larger than I imagined, five to 10 hours between each destination. We only had about two weeks to do the trip, so we came to the ecologically dubious conclusion that we would have to fly. The problem, we soon found out, is that there are virtually no direct flights between these places. Every trip has to go through Mexico City. What’s more, several locals warned us that Mexican airlines can be unreliable, particularly the low-fare carriers. But time was running out. Tickets were getting more expensive. It can’t be that bad, we said. It will still be faster and easier than driving.

We were wrong. Nearly every leg of the trip went somehow astray. The takeaway? Don’t make the same mistake we did and try to pack too many destinations into too little time. Either use ground transportation, stick to the national carrier Aeromexico, or build in time for delays. In the end, we had to skip Troncones, a tiny fishing village and surf spot that’s recently evolved into an under-the-radar haven for bohemian travelers drawn not only to its abundant tropical flora and pristine beaches, but to a growing crop of laid-back eco-retreats. Most notable is Lo Sereno Casa de Playa, a two-story, 10-room low-impact hideaway that sits directly on the ocean at the edge of the jungle.

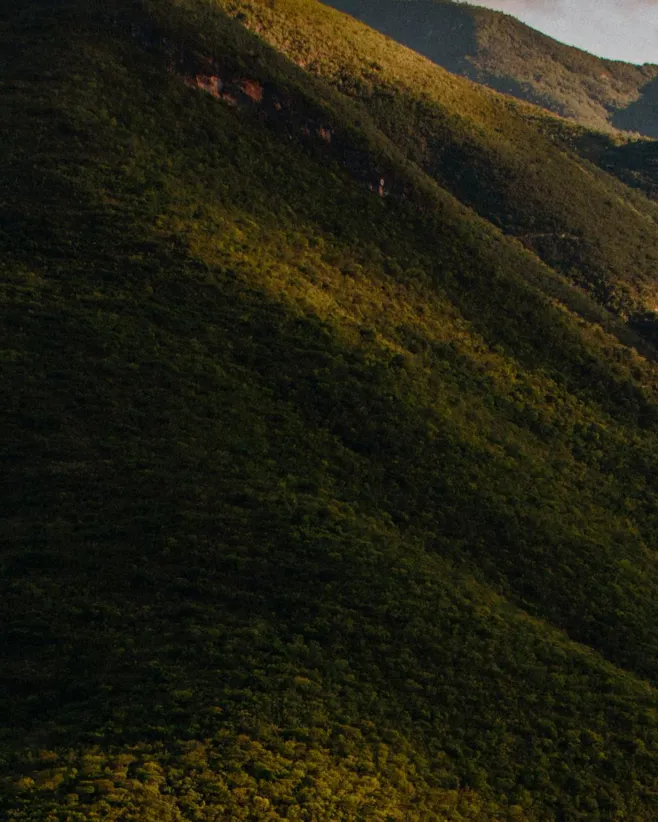

Luckily we made it to Puerto Escondido, and all prior trials and tribulations were forgotten the moment I crossed that green threshold to that nearly empty beach and looked out on the open ocean. Though it’s been slowly growing in recent years as a travel destination, Puerto Escondido, which sits in a fertile bay on the Oaxacan coastline, is still relatively non-touristy, due in large part to the fact that there are no international flights in or out. The area has been inhabited by indigenous people for centuries, but the town dates only from the mid-20th century, and it wasn’t until surfers discovered it in the 1960s that Puerto Escondido (Spanish for “hidden port”) really began to take off.

Pacific coast Surfer's paradise

Pacific coast Littered with world-class surf spots

A laid-back surfer sensibility still prevails, especially around the most popular surfing beaches, La Punta and Zicatela. Palapa bungalows, taco shacks, surf shops, juice stands, and small, quirky hotels and restaurants line the coast. Winding sandy footpaths lead down overgrown slopes to quieter, hidden coves, like Playa Carrizalillo, whose southern exposure makes for gentle waters. But Puerto Escondido’s natural wonders go well beyond the beach.

Our first night, once the sun had set over the ocean, we headed 15 kilometers north to the Laguna de Manialtepec, a biodiverse coastal lagoon filled with mangroves and a stunning variety of wildlife, including pelicans, crocodiles, storks, cranes, jacanas, buzzards, kingfishers, and swans. But Manialtepec is also home to an extraordinary phenomenon: bioluminescence. Tiny plankton that flow in from the ocean have evolved to ward off predators by emitting ultraviolet light when disturbed, literally glowing in the water.

We waited until the last rays of sunlight had faded and set out in a boat with a local guide named Nora, who assured us the crocodiles have no interest in humans. A slim crescent moon hung overhead, glistening over blue-black waters. A new moon would have been better, she explained, but we can still find places dark enough to experience the bioluminescence. We motored deeper into a mangrove-shaded area. The foamy surf trailing off from the boat seemed to radiate faintly. “Put your hand into the water,” said Nora. I followed her advice and saw my hand encased in a vivid blue glow just beneath the water’s surface. The boat stopped, and I dove into the warm, dark waters of the lagoon. Opening my eyes under the surface, I saw countless tiny glowing particles, like a million miniature subaquatic fireflies.

Puerto Escondido The biodiverse Laguna de Manialtepec lagoon

Where the lagoon meets the Pacific Local fishermen cast their lines

As Nora drove us back to the hotel, I asked her what she thought of the highway the government is building to connect Puerto Escondido with Oaxaca city, making what’s now a rough but scenic seven-hour drive through the mountains into a two-hour straight shot. “You know, when I was coming here from Mexico City for vacation, I was so excited about the highway,” Nora said, “but now that I live here, I pray that they never finish it. It’s a very quiet place, beautiful, safe, with so much nature.” Over the course of our visit, I spoke to several other locals who all expressed a similar sentiment. They don’t want mass tourism, they said, and they worry increased accessibility could also attract cartel violence, which is a problem in other regions of Mexico. I couldn’t help but join Nora in her prayer.

I awoke the next morning in my private palapa bungalow at Hotel Escondido and took a moment to soak in my surroundings. Opened in 2013, the hotel is the work of architect Federico Rivera Río, who set out to update “ancestral architectural forms,” using local, sustainable materials and techniques. Each bungalow has its own ocean-facing terrace and plunge pool. Some 60 percent of the hotel’s energy is solar, and water from a well is pumped and redistributed across the property. The kitchen is helmed by the Nayarit-born chef Saul Carranza, who worked at world-famous restaurants like Nobu in Malibu and Pujol in Mexico City before coming to Puerto Escondido.

Saul Carranza Nayarit-born chef of Hotel Escondido

Marlin tostada with cilantro One of chef Carranza’s popular dishes

Oaxacan cuisine is world-renowned, and I had several excellent meals during my visit. But none was better than the food at Hotel Escondido. Highlights include Carranza’s green ceviche, a spicy, sour, tantalizing mix of fresh-caught fish, tomatillo, lime juice, and habanero chili, and what must be one of my all-time favorite breakfasts: the Huevos Escondido, a handmade corn tortilla stuffed with organic eggs and covered in mole, that deep, rich, complex sauce that’s one of Oaxaca’s best-known culinary exports.

“All of my staff live in the community close to the hotel, so they showed me this style of mole from the coast. Some of the other dishes I learned from my aunts, from my grandmother, my family in Nayarit and Michoacán,” said Carranza. “I mix all these things together in these dishes. But you know, my kitchen staff are so important. I learn from them and they learn from me.”

On our last day in town, we woke up before dawn and drove an hour down the coast to watch the sunrise in San Agustinillo, a small fishing village where Grupo Habita will open their next hotel toward the end of 2020. The village’s 1,300-meter-long golden sand beach is hedged by hills and steep cliffs that prevent the construction of large developments. Only low-impact, eco-properties are possible, assuring that this undulating strip of ravishing coast will remain unspoiled.

Hotel Escondido Oaxaca Sits in a 19th-century colonial residence

Hotel Escondido Oaxaca Opened in December 2019

The preceding article is excerpted from the 2020 edition of Directions, an annual magazine by Design Hotels that looks at movements underway in art, design, food, wellness and fashion, and how they affect the way we live and travel. This year’s issue explores the motivations, values, and desires of the Promadic Traveler of tomorrow—one who does not ask where to travel, but why.