Words Vidula KotianDate 12 February 2024

said American marine biologist and writer Rachel Carson. What if you could reap the benefits of going out into a forest while being indoors where most of us spend the majority our time? First termed by German social psychologist Erich Fromm in 1964 and popularized by American biologist Edward Wilson in 1984, biophilia—“the love of living things” in Greek—was a reaction against nature-isolating urbanism.

Erich Fromm on Biophilia

Biophilia is humankind’s innate biological connection with nature. In architecture and design, such spaces can reduce stress, improve cognitive function and creativity, improve our well-being, and expedite healing. Buildings overflowing with plants cast a bucolic picture but true biophilic architecture is more than just an image. It involves integrally incorporating plants, flowing water, biodiversity, natural materials, and plenty of sunlight into everyday spaces.

Prime examples Barbican Centre and Atri House

One of the most famous examples is the “brutalist hanging gardens of Babylon” as the Barbican Centre in the heart of London is sometimes described. One of Britain’s most radical postwar buildings, the complex offers a remarkable variety of experiences within a single building, such as vast areas of water (lakes, ponds, waterfalls, and fountains) interspersed with quiet nature reserves and parks with mature tree plantings. The creation of these green spaces within the estate have allowed a rich bio-diverse eco-system to flourish.

Outside of Tulum, Mexico, SFER IK completely subverts the idea of what a museum should look like. Nestled deep in the Mayan jungle, the arts center is primarily made up of living trees, vines, and local timber. The work of entrepreneur, philanthropist, and self-made architect Eduardo Roth, SFER IK gets its name from its curvilinear design (pronounced the same as “spheric”) and the building is in almost every way an extension of the jungle that surrounds it. “It’s not hermetically sealed like a typical art gallery. If it rains, some water gets into the flowerpots and trees,” says Roth.

SFER IK The project won the 2020 LCD Berlin award for New Culture Destination of the Year - Latin America

Main components The structure is made from zapote wood, fiberglass, vine, and cement

Integrated nature The construction did not impact the jungle in any way

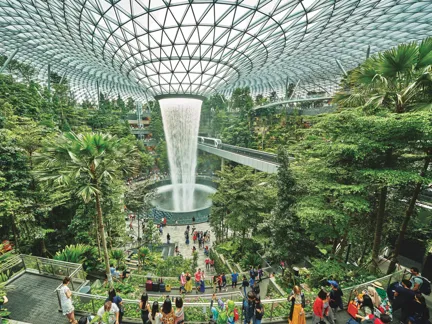

As a city state, Singapore is the poster child for biophilic design, with architects and designers reinventing new ways to live with the natural world. Starting from the Jewel Changi Airport, which houses Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie's vision of paradise: the world’s tallest indoor waterfall surrounded by a lush garden populated by thousands of trees, palms, and shrubs that span 120 species. Other projects of note that echo the tiny island’s reputation as a nature-infused city-state are the Gardens by the Bay and the Funan integrated development by UK-based landscape architecture firm Grant Associates—both featuring ample, accessible terraces and rooftop gardens that refresh the mall and office block typology.

On a more personal scale, Swedish company Naturvillan are creating homes like the exquisite Atri, a climate-smart A-frame villa in Brålanda, Sweden, with its own system for energy, water, and nutrient recovery from wastewater completely off-grid. Inspired by nature, the triangular house integrates seamlessly with its surroundings, where its grand atrium and sliding door merge with the greenhouse and living spaces to create a sense of spaciousness and flexibility. With two floors plus a rooftop terrace, the house offers panoramic views of the forest and Lake Vänern that are unparalleled.

Gardens by the Bay The Cloud Forest is one of the tallest indoor waterfalls and mountain with plants from around the world

Supertrees Rising up to 50 meters, the iconic giants provide shade in the day and light up at night

Hedge Maze The largest maze of its kind in Singapore

Jewel Changi Airport The Rain Vortex features a seven storey waterfall

Moshe Safdie on Jewel Changi Airport

Innit Lombok View of the villas with sand-floored living areas on the ground floor

Ekas Bay Innit is located on Southeast Lombok

Even in the world of hotels, biophilic design can bring a revolutionary approach to interiors, fostering a multisensory connection with the world around us. Take, for example, Innit Lombok, set on a secluded stretch of white-sand beach in Lombok. Designed by renowned Indonesian architects, Andra Matin, Gregorius Yolodi, and Maria Rosantina, the seven-beach-house haven harmoniously blends with its natural surroundings while incorporating unique architectural designs, such as having sand-floored open-space living and dining areas on the ground floor of the villas.

In the heart of Kyoto, Genji Kyoto showcases how gardens can be an important element of a hotel’s spatial layout, dissolving the boundaries between interior and exterior spaces. Here, the floorplan is oriented in such a way that every room has scenic views of the river and mountains, the city, or tranquil private gardens.

Genji Kyoto Nestled on the banks of the Kamo River

Outside in Gardens are an important element to the hotel’s spatial layout

Set on a beautiful lagoon in Bacalar, Mexico, Boca de Agua presents a new, conscious form of hospitality—one where the stunning nature is at the focal point of the experience. Tropical-sustainable modernism at its most inspired, treehouse-style villas allow flora and fauna to thrive below while giving a front-row view to the bountiful jungle outside. Everywhere you look, the hotel’s structures seem to meander around the nature rather than the other way around.

As the world population continues to urbanize, incorporating nature as an integral part of architecture and design will be ever more important. It is why crackling fires and crashing waves captivate us; why a garden view can enhance our creativity; and why shadows and heights instill fascination and fear. As Frank Llyod Wright once said, “Stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”