A mental packing list of sorts, The Good Traveler lays out our aspirations on the path to becoming more respectful, considerate travelers. To learn how these ideas can shift and shape our journeys, we have invited ten travelers we admire to go into the world and explore each tenet.

Words Christian Näthler Images Christian NäthlerDate 24 November 2023

Do you remember, back in the 2020-2021 Anthropause, when nature was healing? Wildlife reclaimed our suddenly barren urban spaces, aquatic environments reassumed their pristine state, our air achieved peak breathability, and dinosaurs experienced a resurrection, gallivanting through Times Square.

“In the absence of people living in ignorant, dangerous, mindless, and heartless ways, the earth began to heal,” as the pandemic’s poet laureate, Kitty O’Meara, wrote. It wasn’t long before that narrative was debunked. Voices of reason rushed to dismiss Venetian dolphin sightings and other such viral untruths as nothing more than meme fodder.

Certainly, humanity’s brief indoor confinement hadn’t spurred some sort of mass rewilding event (although, air and water quality did improve in many places). Besides, there was always the problem that eventually the pandemic would end and we’d rush right back to our ignorant ways—except even more mindlessly, to make up for lost time.

Tourism, meanwhile, was due for a shift in collective consciousness. “When borders do reopen, a more mindful approach to travel will likely be top of mind: fewer trips, longer trips, more meaningful trips,” Sarah Khan predicted in Vox. The aspiration went beyond sustainable travel, which merely encourages going somewhere without making it worse. What the moment demanded was for travelers to actively nourish the destinations they visited. Wanderlust, but make it regenerative.

Christian Näthler

Christian Näthler is a German-Canadian writer currently living in Berlin. His journalism work explores digital solutions to the climate crisis, conscious travel, and sports culture. Through his newsletter, lol/sos, he publishes interviews with analogue creators as well as personal reflections on our generation’s fraught moment in time. He envisions his future office to be a gourd patch on a permaculture farm.

Numbi Valley is named after the surrounding foothills of the Swartberg mountain range (“numbi” means “boobs” in Siswati)

In essence, it insists that our being on the move should contribute to the positive co-evolution of local communities, economies, and the natural environment. Any meaningful progress to that end requires green-mindedness not only from travelers, but from all stakeholders in the tourism sector—tourists, regulators, NGOs, transportation providers, hotel developers, tour operators, environmental groups, and media—who all play a crucial role in harnessing our mobility as a force for social and ecological good.

In many ways, it’s the logical progression of a broader reckoning that existed before the pandemic. “With movements like ‘flygskam’ or ‘flight shame’ gaining momentum since 2018 thanks to environmental activists like Greta Thunberg, younger generations are more conscious of travel’s impact,” says Bárbara Büchel, whose company, Viatu, caters to this new class of travelers.

The permaculture farm is entirely off-grid— gas stove, solar power, groundwater

Together with guilt and empathy, shame constitutes a part of the wide spectrum of emotions that inspire prosocial behaviors like sharing, donating, cooperating, and volunteering. For all its aspirational overtones, regenerative travel is also about correcting an error.

I, too, had been contemplating my travel choices, increasingly questioning how they could enrich the places I was visiting. How can I ensure my money benefits local businesses, particularly during the off-season when they face income fluctuations? What should I know about the destination’s ecology? How can I support conservation efforts? Where might I be a nuisance no matter the goodwill of my intentions?

I gave little thought to these considerations for the better part of my traveling life. When I went somewhere, I was primarily concerned with enjoying myself. But there’s a limit to that, as I eventually discovered. After several very nice trips—azure waters, beautiful sunsets, great food—I began to suffer from a sort of leisure ennui. My girlfriend, who’d always been conscious about her travel choices, was also seeking for a more immersive way to spend an extended period abroad. And so it was that, this past winter, we happened upon a unicorn opportunity in the nascent world of regenerative travel.

We arrived in early January, known locally as peak summer. For four weeks, we would work on an off-grid permaculture farm in the semi-desert of South Africa’s Klein Karoo. A six-hour drive from Cape Town, the region is home to some of the most prolific ostrich farming in the world. Two decades ago, when the owners bought the land, there was no reason to believe anything could grow there. Giant birds grazing all over the place is notoriously bad for soil. The prospects for biodiversity were essentially hopeless. But permaculture, with its emphasis on biomimicry, offered a lifeline.

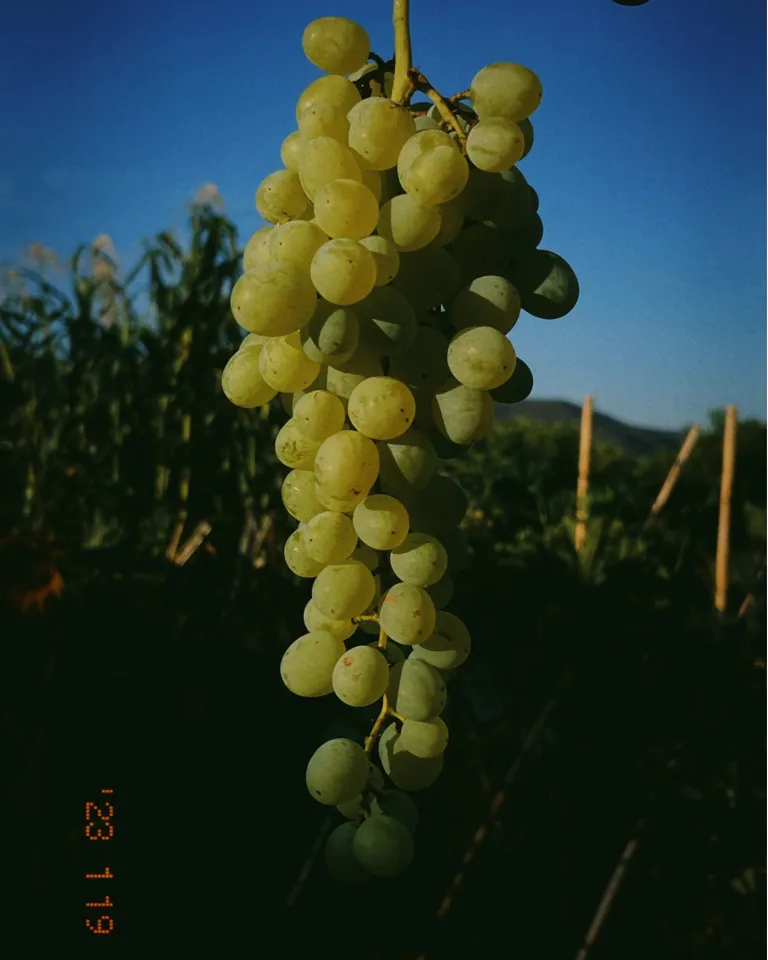

A morning's harvest being prepared for neighbours to pick up

By working in harmony with nature rather than against it, permaculture seeks to rejuvenate soil, restore ecoystems, and create sustainable food production systems. At its core is a set of 12 principles, encompassing concepts like observation, diversity, efficiency, and circularity, to achieve a mutually beneficial bond between humans and the natural world. What the owners lacked in fertile land they made up for with a recipe for regeneration. Today, the formerly degraded terrain is home to one of the lushest and most productive farms in South Africa.

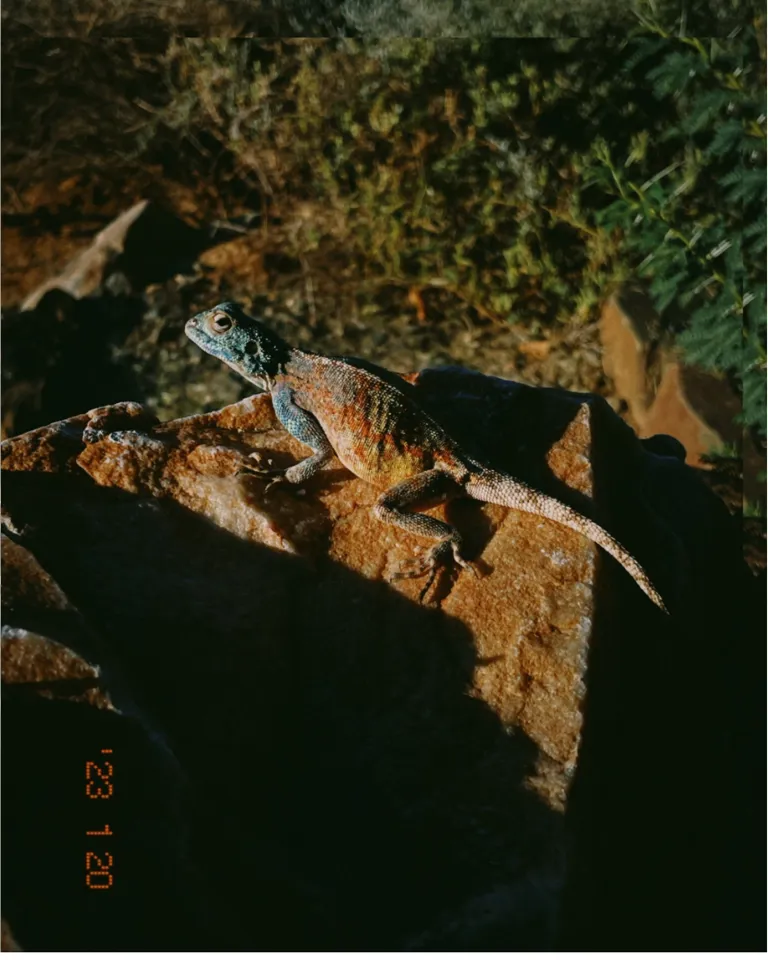

During the first week, the owners taught us how to keep everything nice and alive, including ourselves. We learned how to harvest energy from the sun and water from the earth for everything from solar cooking to irrigating the food forest. We were told nature has solutions for most of our problems, like the time a flock of panicked birds alerted us to the presence of a highly venomous snake.

We were shown how to reincarnate objects and materials otherwise deemed trash. We were awakened to the potential of previously underappreciated circular assets. Consider chickens: They happily ate our food scraps and, in return, fertilized our soil and provided eggs we could eat or sell to the neighbors. It only took a few days to develop a kinship with them and every other living thing.

The author's girlfriend, Eva, shaking down an almond tree.

After a week, the owners went on holiday, entrusting us to steward their oasis. Immediately, our work hours doubled, up to 14 a day. For the first time, my labor felt alive and necessary. We didn’t just mitigate or sustain; our presence there, brief as it was, genuinely enriched the various systems with which we harmonized.

We improved the soil, provided the community with nutritious food, seeded and nursed the next generation of resilient crops, supported wildlife (tortoises drank from our watering holes, mosquitoes from our blood), provided sustainable visits for dozens of guests, and developed mutually supportive relationships with local residents—all while producing essentially no waste and having the time of our lives.

Twenty years ago, the land was barren, decimated from generations of ostrich farming

Most of all, it was redeeming to see first-hand that our role in the environment can also be an overwhelmingly positive one—a welcome departure from my belief that humanity is destined to proceed until everything is wrecked and everyone is gone. Our time on the farm not only exposed us to a better way to travel but also a better way to live. We saw the type of future we wanted for ourselves and came away with a blueprint for how to make it happen.

Of course, I’m not naïve to the environmental implications of having flown to Cape Town, driven hundreds of miles to an isolated property, stayed for a month and, in a roundabout way, aspired to offset the impact. At the same time, the footprint of domestic trips, like going to the grocery store, often escapes us. “We are all travelers in the world the moment we leave the house,” says David Leventhal, a regenerative impact entrepreneur and investor. “Recognizing this enables us to take more regenerative actions in our travels of any distance.” It’s about a whole systems approach, he says, pointing out the hypocrisy of condemning air travel while driving an electric car to a hotel blasting air-con constantly, and flying in food from all over the world.

Figs ready to be sun-dried into a natural snack

Everything grown on the farm is consumed, sold, or re-integrated, leaving no waste

In the next decade, my girlfriend and I plan to start our own permaculture project, which will include a food forest grown on regenerated land. It is the most effective way we can have a positive influence on our environment. According to Project Drawdown, a science-based non-profit that seeks to accelerate our fight against climate change, food systems hold the greatest potential for reducing carbon emissions. Remarkably, the two most impactful solutions across all sectors relate to food. Permaculture, by designing food waste out of the system and prioritizing a plant-rich diet, embodies both of them.

On an industry level, then, regenerative travel goes beyond reshaping tourism. It involves harnessing travel's unique capacity for transformation to determine how and where you can most effectively drive change. Journeying out into the world, as always, leaves an indelible mark; it gives you something to bring back. “Being on vacation allows people to gain perspective about how they live at home and can make changes in their lifestyle to live more regeneratively,” says Leventhal. “Change happens little by little until it happens all at once.”

The lesson for me is that we don’t need an Anthropause for nature to heal. In permaculture, we have a framework for being responsible chaperones in this process. It starts with understanding the unique dynamics of the places we populate (permaculture principle #1), followed by small, slow solutions (#9), and adjusting as needed according to feedback by nature (#4). Every trip we take, near or far, is an opportunity to have a regenerative impact on our surroundings. The first step is out your front door.

Daytime temperatures in the Klein Karoo regularly exceed 30 degrees C