A mental packing list of sorts, The Good Traveler lays out our aspirations on the path to becoming more respectful, considerate travelers. To learn how these ideas can shift and shape our journeys, we have invited ten travelers we admire to go into the world and explore each tenet.

Words Katie McKnoultyImages Katie McKnoultyDate 16 February 2023

“Yours please!” I reply, delighted to be buying casually-organic produce, picked this morning from a garden a few hundred meters from where I stand. We stay here surrounded by all the fruits and vegetables of the season, discussing each thing I want to buy in detail, her carefully choosing the perfect specimen of each. There is no rush and our interaction lasts 15 full minutes but I’ve learned to enjoy this time and not let my time-is-money, city-life brain hurry me. There’s a line out the door four people deep but when I exit they each greet me warmly, not a trace of annoyance on their faces.

I’m here for the whole summer in Fratte Rosa, a small hilltop town of less than 1,000 inhabitants in Le Marche, Italy. Despite being in the center of the country, this region is often overlooked by Italians, and unknown to most foreigners; the lack of good train and plane connections makes it pretty inaccessible. But I always had a feeling the local Marchigiani liked it that way. Their unassuming way of life is focused on the good things—family, food, friends, nature, and other simple pleasures. And it was able to go on relatively undisturbed in the absence of globalization or over-tourism. There’s no bucket list of things to do here either. That’s why I like it. To me, the best way to experience Le Marche is to slip into village life, noticing and delighting in the daily rituals of a life lived slowly, hoping it will rub off on you in some way.

an Australian writer, photographer, and creator of the blog The Travelling Light. Her work as a travel writer, photographer, and brand marketing consultant centers around unique, positive places and people carving out their own path in life, promoting and supporting a more sustainable, conscious world.

I’d visited this region before but never for this long—I was planning to stay for three months, maybe more. After years spent living all over as a digital nomad and finally settling in densely populated, frenetic Paris, burnout had gotten to me. I’d come to this part of the world to slow things down for the summer. And I’d come to this particular town because I’d met a guy, Filippo, who lived in this deliciously slow place, a mountain man who knew how to build things and grow things. He drove a Fiat Panda to pick me up at the coastal train station whenever I visited from Paris, a contented, relaxed smile on his face, one I wanted to see more of. It was the kind of smile I wanted across my face, too. I’m here to see if it could work—us and me in this slow, quiet place.

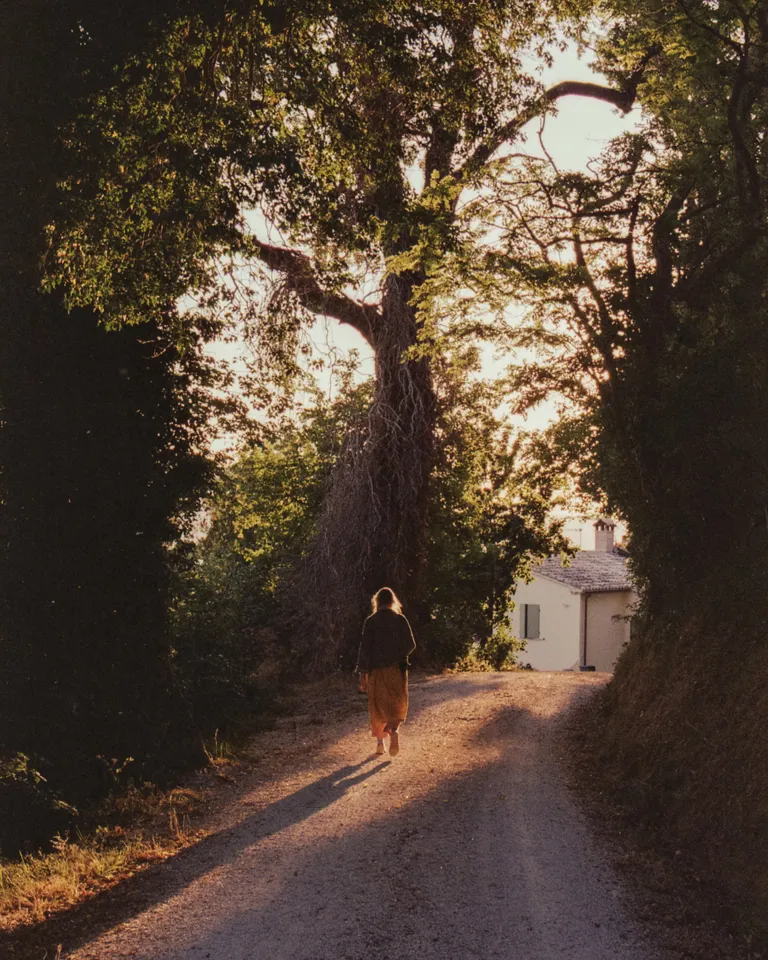

My first lesson in slow, summer living in Italy is the importance of the daily passeggiata, or walk. Taken in the late afternoon or early evening after the sun has lost its bite, it follows another of my new favorite rituals, the afternoon nap. I head out every day to a place the locals call “the most beautiful street in the world,” an undulating road rising in a sea of green patchwork hills, far-off mountains, country houses, and open sky. My walk becomes a pivotal part of my day, a stretch of time where there is no goal, no place I’m trying to reach, where I’m just putting one foot in front of the other, wandering and marveling.

I fill up each morning of my week with a roster of local food-purchasing activities to replace the supermarket: On Tuesdays, the closest town hosts its market. On Wednesdays, the butcher cooks his porchetta, roast pork, with a retro sign declaring “porchetta oggi, “pork today,” propped up alongside a larger-than-life cardboard pig. On Fridays, the fish van brings us caught-this-morning seafood from the Adriatic and on Saturdays, the fresh produce shop gets its delivery of crunchy, green spinach with dirt-covered leaves. I visit Filippo’s friends in the winery outside town for their organic wine made from the grapes I regularly pass on my walks. Another of my walking routes takes me past the broad bean farm where I often stop for all my broad bean needs. This ecosystem of real people supporting real people, not corporations, and eating the food growing on my doorstep gives me a sense of pleasure a trip to the supermarket never has. Plus it tastes really good.

There’s also a season for everything to grow, ripen, and die, and I get to see it up close for the first time. In early June, fields of chamomile flowers spring up, their perfume wafting in through the car window. One morning, Filippo pulls over and I pick a bunch, drying them in the sun for weeks and scooping them into a jar for future teas. The onions blossom like flowers too, we roll the windows up urgently as we pass them, the smell too much to bear. Later that month, the sunflowers sprout, getting taller and taller with every day. By July, they’re fully grown and towering over my head. By mid-August, I’m blackening my fingers picking wild blackberries growing in prickly bushes by the roadside. The figs ripen towards the end of August and one day Filippo parks his scooter and runs across a farmer’s overgrown field under the cover of tall grass, relieving the tree of a handful of figs. I start to appreciate just how long it takes each piece of food to become an edible thing, and what a shame it is to let any of it go to waste.

I start to notice Filippo’s nonno’s car parked outside the town bar every afternoon. Concerned, I enquire only to find that he comes here every afternoon from exactly 2:30 to 4:30 pm to play cards with his friends. The older (and sometimes younger) men huddle around a square table where two players duke it out playing scopa. Tense anticipation hangs in the air followed by shouts of dismay or gleeful victory, piercing the quiet of the town’s afternoon siesta. The same players congregate at the bar’s evening bocce court every night after dinner. I spectate alongside the others with a gelato in hand in the warm evening air. The pleasure of a shared pursuit, of being together, of making time to play games even though you’re a 35-, 75-, or 95-year-old adult was one I’d apparently been missing out on.

A lesson I learn in slow travel is that some places only make themselves known to you with time and relationships, uncovered over the course of conversation and the building of trust. One such place is the secret river that flows through the center of Northern Marche, made of freezing water streaming down from the mountains. So precious is this place that I am sworn to secrecy on revealing its location to anyone else, no Instagram geo-tagging allowed.

Making my way down the hill through the trees, I spot a group of teenage boys staking out a wooden picnic table half submerged in the stream. Kids take turns jumping from the high rocks, another group of boys play cards in the shade. Beautiful, god-like tanned 20-something Italians lounge in groups on the rocks. We cool our B.Y.O. beers in the frigid, crystal clear water and magical insects the brightest blue I’ve ever seen land delicately on bright green leaves as I laze in the shade reading. I marvel at how only those who stay longer, interact, and ask around get to know unreal places you won’t find in a guidebook.

At the end of the summer, I decide to stay in this slow place for longer. Three and a half years on, I’m still here, this slow life is my everyday life, with Filippo. The experiences I had can only really be found if you travel slowly and go deeper into a culture. But slow travel is a way of being, not a length of time, despite what the name suggests. You don’t need months. It’s how you choose to spend your days in a place, your mindset as you explore, as you plan or don’t plan, your day. Slow travel is being in a place when you travel, experiencing everyday life in a different way and having that be enough.