A mental packing list of sorts, The Good Traveler lays out our aspirations on the path to becoming more respectful, considerate travelers. To learn how these ideas can shift and shape our journeys, we have invited ten travelers we admire to go into the world and explore each tenet.

Words Claire Mouchemore Date 23 January 2024

In January, I set off on an idyllic trip through Mexico to escape the European winter. In 35-degree heat, two piña coladas deep, while lazing atop a sun lounge on a beach off the coast of Puerto Escondido, I was laid off from my job.

I was absolutely devastated and scared of what uncertainty lay ahead. On top of that, I was going through a painful and drawn-out breakup and didn’t have a place to live when I arrived back in Berlin. As the saying goes, bad things come in threes, and it’s hard to feel connected to yourself when everything seems to be in a state of flux.

Determined to enjoy the rest of my trip before returning to sub-zero temperatures, I jumped on my phone to execute my usual Google keyword search: Queer spaces, queer bookshops, queer bars, queer clubs and queer things to do in Mexico City. Puerto Vallarta is known for being the gay capital of Mexico, but at this point, I was over the beach and keen to head back to Mexico City for the remainder of my trip.

Claire Mouchemore

Claire Mouchemore

Claire Mouchemore is an Australian writer, researcher, and educator living between Berlin, London, and Melbourne. Her writing traverses music, fashion, film, food, travel, art, and how each intersects queerness. Among other things, she is an avid reader, queer activist, design dilettante, wine epicure, music maker, and ocean admirer. Her work has appeared in Vogue, VICE, GAY TIMES, i-D, Boiler Room, CRACK, and more.

Queerness has always been my main jump-off point for finding community and connecting with people who make me feel seen and understood. As someone who often travels solo, I look to connect with people in the places I feel most at home—bookshops, bars, community spaces, galleries, museums, and clubs.

After touching back down in Mexico City on a Saturday afternoon, I was craving a mezcal margarita, so I began my journey towards Travesura, a quaint queer bar just north of the neighborhood of Doctores. At Travesura, a lesbian flag adorns the entryway into the bar, and a trans flag hangs above the DJ booth, two small but lasting sentiments which evoke an instant feeling of belonging. Inside, the walls are covered with brightly colored paint and the bathroom is plastered with stickers sporting phrases that translate to “I see a powerful woman” and “fist the patriarchy!”. The bar hosts small club nights and events, as well as moonlighting as a tapas restaurant serving tostadas, ceviche, and empanadas to local families and queers that pass by throughout the evening.

It occurred to me how rare it was for families from the local area and members of the queer community to have a space that caters to and welcomes them both. Upon striking up a conversation with the family across from me, I learned they live a few streets away and come by on a weekly basis. Back at the bar, unsure of where my night was headed, the bartender gave me an address for a party happening later that evening.

Following the bartender’s recommendation, I made my way to Juarez, a neighborhood that’s home to Zona Rosa, ‘the pink zone’, Mexico City’s queer neighborhood (or gay-borhood as I like to call it). At around one in the morning, I entered [sic] community club, a three-floor venue that hosts weekly raves, labeling itself a “nocturnal playground for the queer.”

Inside, shirts were well and truly off, ravers were sweating profusely, and the sound of house and techno reverberated through bodies that pervaded the main floor. On the other side of the venue, I found myself drawn to a smaller room with a bar at one end and a drag queen at the other, behind the decks dropping acclaimed R&B edits and queer house anthems to the enthusiastic group of punters that crowded the booth, moving back and forth with zeal. There, a trio of dancers welcomed me into their group as we belted out the lyrics to Megan Thee Stallion’s Savage mixed into a UK Garage track. While we stood in line for a beer, they told me they’d been coming to [sic] every Saturday for the last year, because, “it’s unlike any other queer night in the city”.

Some of my most formative experiences have taken place on the dance floor. The act of dancing, letting go and connecting with others, sound-tracked by thumping dance music, has led me to meet some of my closest friends.

The next morning, slightly hungover and tired, I roamed the markets of Coyoacán on the outskirts of Mexico City. After wandering alleys filled with trinkets, food, art, and jewellery, I purchased some traditional handmade Oxacan ceramics to take back home; bowls to store diamond salt and serve various dishes at my next dinner party. Following a snack pit stop to ensure I hit my daily Al Pastor quota, I ventured beyond the market to community space and bookshop Librería U-Tópicas. Inside, the space is decorated with illustrations of feminist and queer elders, including Stonewall veteran Marsha P. Johnson and writer and activist Angela Davis. The choice of interior makes sense: U-Tópicas, which opened in 2018, houses over 2,000 books on decolonial feminism, gender studies, politics, sexuality, and motherhood.

I endeavor to visit a bookshop within 24 hours of arriving in a new city. There’s something about being surrounded by books that makes me feel at home instantly. Perhaps it’s because my bookshelf is as extensive as that of a bookshop, though I’d like to think it’s more to do with the inspiration and strength I find in learning about queer history and those who pioneered it. As the attendant working behind the counter at U-Tópicas processed my purchases—a copy of Leslie Feinberg’s Transgender Warriors and Jack Halberstam’s Female Masculinity—we got chatting. I detailed my mission to unlock new levels of queer joy, to which they suggested a visit to a gallery in the heart of Roma Sur.

For the last century, the work of queer artists Frida Kahlo, Rodolfo Morales, Nahum B. Zenil, and Julio Galán has lined the walls of various institutions across Mexico City. While their contributions to the art world are essential, much of their output doesn’t reflect what it means to be queer and Mexican in the 2020s. Campeche, however, is a more recent addition to the art world. Opened in 2020, the gallery aims to champion under-represented voices by focusing on platforming queer artists.

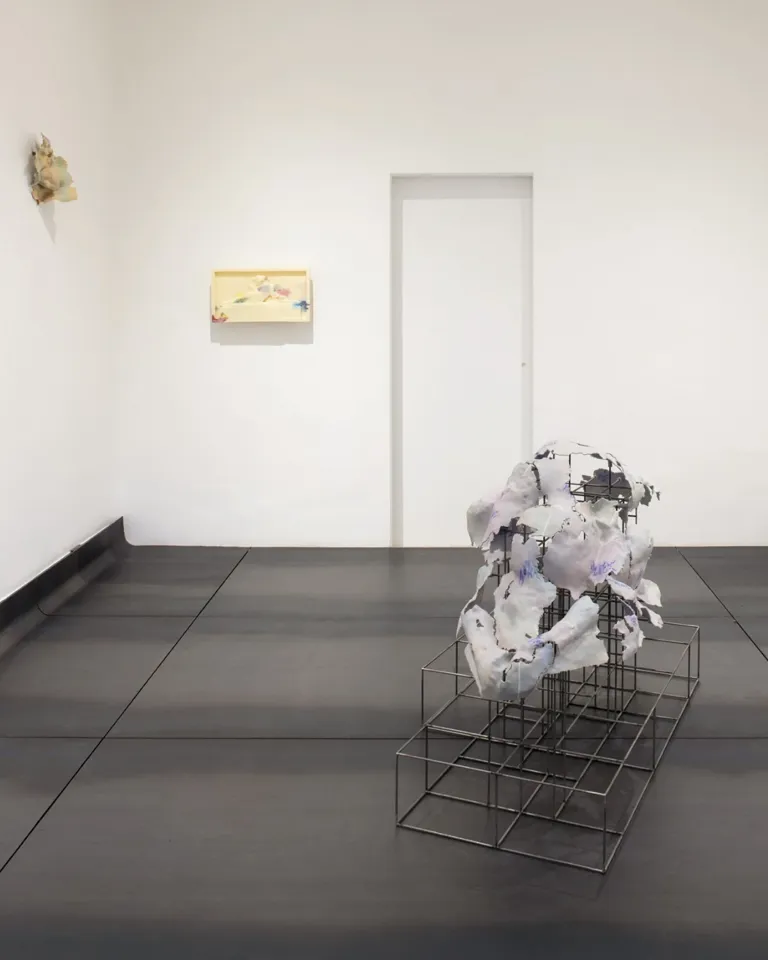

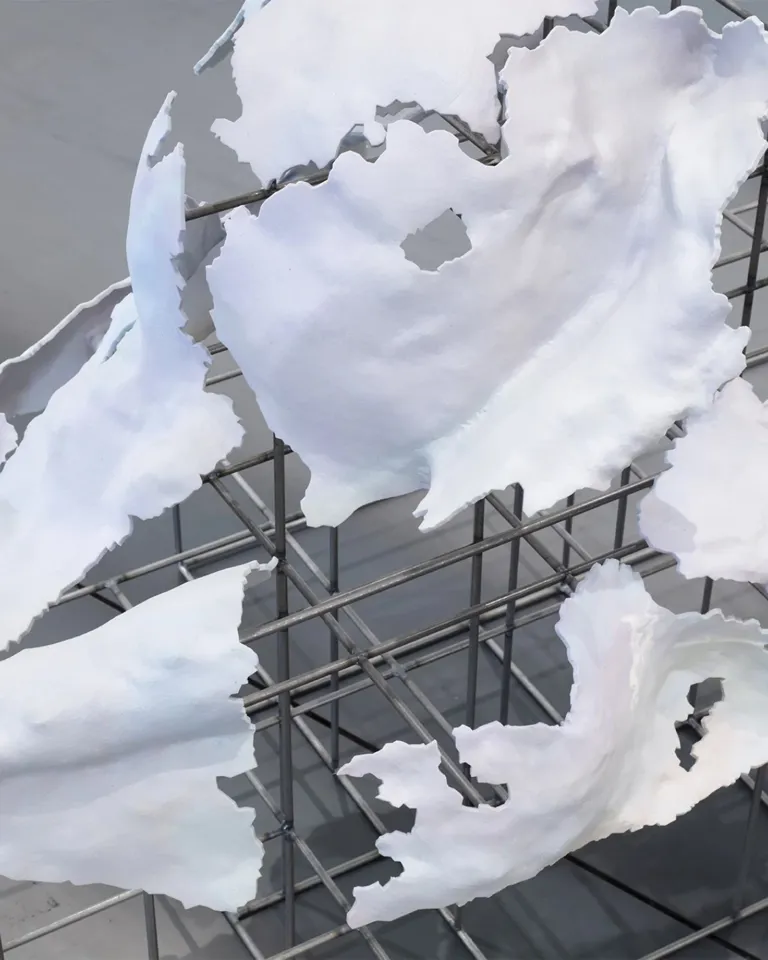

Desesperanza, 2021, 3D-scanned arsenic, steel 143 x 80 x 95 cm, Edition of 2 + 1 AP (2/2) Courtesy Galeria Campeche

Desesperanza, 2021, 3D-scanned arsenic, steel 143 x 80 x 95 cm, Edition of 2 + 1 AP (2/2) Courtesy Galeria Campeche

When I visited the space, Julieta Gil’s solo exhibition Revertir el Desgaste, which translates to Reverse Wear, was on show. Julieta’s work explores activism, protests, and power structures through sculpture, video, and mixed media works. In the exhibition, she is quoted as saying, “to observe is an act of resistance,” which I saw reflected in the experiences of the activists she references, who in August 2019, gathered en masse to demand justice for the predominantly women suffering from gender violence across Mexico.

As the weekend drew to a close, I realized my circumstances hadn’t changed—I was still dealing with the loss of a job, mourning a relationship, and navigating the precarious housing market back home. When I arrived back in Europe, I still needed to face all those things head-on. But I was feeling more like myself. The people I’d met along the way had guided my experience and offered an ear, a story, or a word of encouragement to get me to where I was headed next. In times of uncertainty, I always turn to my community to find joy and solidarity. Leaning into the instability of my situation allowed me to find joy in escapism until I was ready to surrender to the unknown.