Words Vidula KotianDate 20 September 2021

The functional aspects have therefore become an essential part of a design itinerary that centers on the geo-morphological experimentation of a building. The physical and intellectual construction of the winery pivots on profound and deep-rooted ties with the land, a relationship that is so intense (also in terms of economic investment) as to make the architectural image conceal itself and blend into it. Below are six stunning examples of European wineries reimagined for the 21st century by the foremost innovators of architecture.

Puurs, Belgium

A contemporary tribute to the typical old Flemish agricultural buildings in the rural area of Klein Brabant, Vincent van Duysen’s first winery is an architectural experience of openness. The main volumes are scattered around a pebbled courtyard, creating a monochromatic presence that strikingly contrasts its green natural surroundings. The main building retains characteristics of a Flemish farmhouse while spreading out horizontally and integrating modern materials, such as concrete and dark timber for a timeless and adaptable aesthetic.

Monolithic concrete walls Image by Koen Van Damme

The lava stones were chosen to match the concrete Image by Piet Albert Goethals

Large sliding-glass openings connect the interiors to a lava stone courtyard dotted with poplar, willow, cherry, and hazel trees—a central part of the estate where workers and visitors can gather and mingle around in after a day of work in the fields. The color tones used for the winery reflect those of the soil of Valke Vleug, allowing a continuation between the terroir and the architecture, between the indoor and outdoor spaces, with only the metal-clad black wooden roof structure above.

Gavorrano (Grosseto), Italy

Best known for his groundbreaking urban designs like the Shard and Centre Georges Pompidou, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano has designed a red-brick modernist winery in his native Italy. Situated on Tuscany’s rocky Maremma coast, surrounded by vineyards, the La Rocca winery produces Baffonero, one of Italy’s finest Super Tuscan wines.

Piano’s iconic design draws on both traditional Tuscan architecture and a chic industrial aesthetic. The slender central tower wistfully reminds one of the ancient watchtowers that dot the Maremma coastline, yet every detail has been finely tuned to facilitate the production of the very finest wines. Overhangs provide shade on the vast terraces for workers and visitors, while the tower uses heliostats or angled mirrors to reflect natural light deep into the interior of the building. In its choice of materials, principally glass and terracotta, the building itself represents the mix of industrial and traditional processes in winemaking today.

Mix of industrial and traditional The winery is principally composed of glass and terracotta

A sacral space The 40 x 40 square meter cellar stands without the support of columns

Images by © Michel Denancé, courtesy © RPBW - Renzo Piano Building Workshop Architects

Bargino, Italy

An architectural exclamation in the rolling landscape of the hills of the Chianti region of Tuscany, the Antinori nel Chianti Classico winery by Marco Casamonti of Archea Associati is steeped in earth tones and complemented by floor-to-ceiling glass doors, wide terraces, sky-high ceilings, and a few unexpected circular cutouts in the vineyard roof where sunlight soaks the spaces below.

Designed to have a low environmental impact and maximum energy savings, the winery is an unusual and fascinating structure. Practically invisible to the eye, the façade appears as two elegant horizontal cuts in the Tuscan landscape, and among its most spectacular features are the impressive spiral staircase that connects the building’s three levels and the rows of vines that, along with the earth, form its “roof cover.”

Images by Ivan Rossi

Suvereto, Italy

At Petra, Swiss architect Mario Botta went beyond designing an impressive wine cellar—with its cathedral-like center—by also including the outlay of the vineyards in his aim to form a contemporary agricultural landscape. With the belief that the birthplace of a fantastic wine is the vine and its grapes, but also the winery building and the whole estate in general, Botta’s design is characteristically minutely detailed. Everything has a purpose—even the scenic exterior stairway becomes a stage for cultural programs in the summer.

Mario Botta built a contemporary agricultural landscape Image by Enrico Cano

The prolific architect’s signature style is stamped across the building, from the materials (masonry) and the earthy colors, to the ecclesiastical architecture (such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) and the trees on the roof (Évry Cathedral). Most of the outlay of Petra winery ensures best wine practices (such as gravity-flow instead of pumping) and simplifying the working routine of the winery staff. But there is also a spiritual aspect to the wine (in every sense of the word), and Botta’s design reflects this beautifully.

Botta’s signature cylindrical form Image by Enrico Cano

The building ensures best grape practices Image by Pino Musi

Haro, Spain

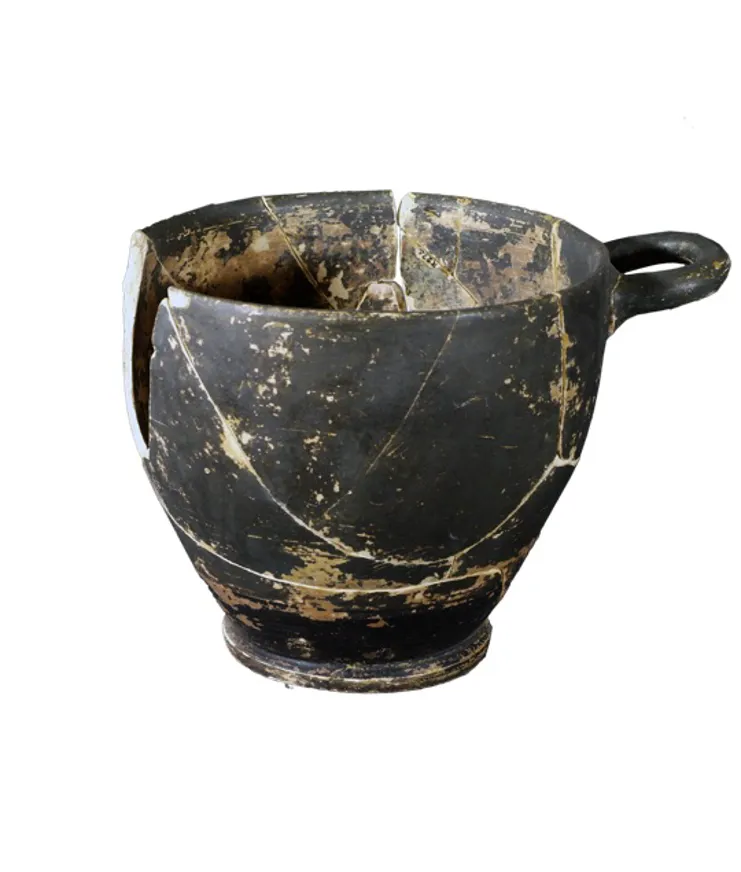

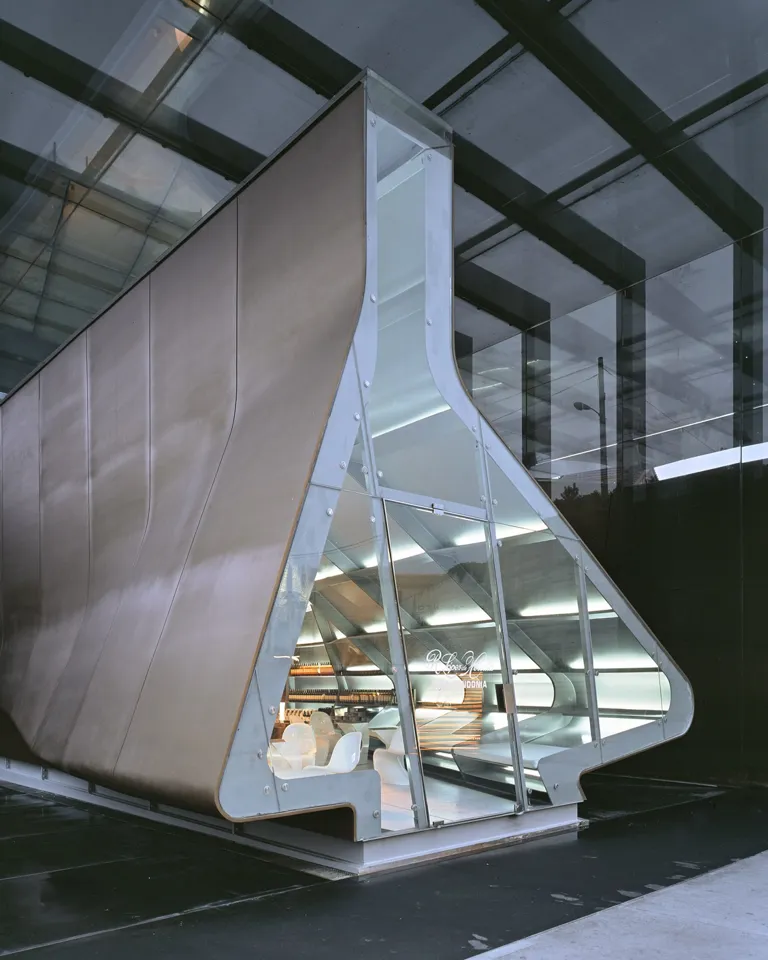

It all started when the great grandfather of the proprietors of Rafael López de Heredia, a venerable winery based in the Rioja region, had a pavilion created for the World Fair exhibition in 1910. Then in 2002, to celebrate the winery’s 125th anniversary, the family commissioned Zaha Hadid Architects to create a new pavilion to contain this older pavilion. The new pavilion was to be exhibited at the Alimentaria Fair in Barcelona and afterwards relocated to the bodegas in Haro.

Made from timber and designed in a fin de siècle style, the old pavilion became a jewel within its new container. Like a series of Russian dolls, the new pavilion was eventually housed within a new extension at the winery—creating another layer in a larger composition. As such, the Pritzker Prize-winning firm’s pavilion was a stepping-stone: a bridge between the past, present, and future development of the bodegas.

The new pavilion by Zaha Hadid Architects Images by Hélène Binet

A modular metallic construction The structure was designed to be moveable

Gumiel de Izán, Spain

The Ribera del Duero region, one of Spain’s foremost wine producing areas, is home to Foster + Partners’ first winery. Built for the Faustino Group, the Portia winery was an opportunity for the Pritzker Prize-winning studio to look afresh at the vineyard building type, using the natural topography of the site to aid the winemaking process and create the optimum working conditions, while reducing the building’s energy demands and its impact on the landscape.

The building’s three wings reflect the wine production stages: fermentation in steel vats; ageing in oak barrels; and maturation in bottles. The wings containing the barrel and bottle cellars are partly dug into the sloping site, reducing energy use and limiting the visual impact of the building on the landscape. Along with many modern design elements, such as Corten steel exterior walls and rooftop solar panels, the structure also incorporates an old-fashioned gravity-driven winemaking system. During harvest, grapes are dropped on the roof, where they are processed and crushed; the juice then pours down to containers waiting below. Bodegas Portia is a building worth knowing—not only for its conceptual beauty but also for its award-winning vintages using the Tempranillo grape.